Hey, you. Yes, I’m talkin’ to you, because I want you to know that there are spoilers in here, both for Watchmen and for Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver. We’re talkin’ about Taxi Driver today because of one cjb@ice.physics.salford.ac.uk, who turns out to be named Christian Burnham. Burnham contributed to the v2.0 Watchmen Annotations, those annotations being a crowdsourced effort built atop Doug Atkinson’s original work. Burnham was the one who asserted way back in my first installment that “Edward Blake is obviously a reference to Blake Edwards,” and that “Rorschach’s methods of terrorism are all taken from Pink Panther movies.”

This time around, he claims that “Rorschach’s opener on page 1 issue 1 is a dead ringer for the dialogue of Travis Bickle in the film Taxi Driver.” Burnham has a tendency to overstate the case, and this time is no exception. While it’s true that both Rorschach and Bickle (Robert De Niro) keep a diary, and that their diary entries are provided in “voiceover” to give us insight into their minds, I wouldn’t call one a “dead ringer” for the other. There are definitely similarities, but also some important differences. Let’s compare styles.

Rorschach: “Dog carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on burst stomach. This city is afraid of me. I have seen its true face. The streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown. The accumulated filth of all their sex and murder will foam up about their waists and all the whores and politicians will look up and shout ‘Save us!’… and I’ll look down and whisper ‘No.'”

Bickle: “All the animals come out at night – whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies. Sick, venal. Someday a real rain’ll come and wash all this scum off the streets. I go all over. I take people to the Bronx, Brooklyn, I take ’em to Harlem. I don’t care. Don’t make no difference to me. It does to some. Some won’t even take spooks. Don’t make no difference to me.”

Both these excerpts begin with shocking language and images. Both indicate a loathing and revulsion for the urban environment. But Rorschach’s opening sentence imitates his speech patterns — clipped sentence fragments, with articles and pronouns extracted, an almost Tonto-ish way of talking. Moore in fact uses this pattern as a tool later on to indicate the psychological split between when Walter Kovacs simply wore a mask and when he became Rorschach, as well as the psychological shift in Malcolm Long.

Interestingly, the rest of the excerpt (and most of Rorschach’s diary) is much more discursive than his usual speech. He spins grandiose, almost biblical images, like this one in which he stands as the vengeful god to punish human sins. Elsewhere, he documents the city as he sees it, or takes notes on the murder case. He even tells a joke.

Travis, on the other hand, is much more prosaic and down-to-earth. He talks about what happens in his job, how much he makes, and recounts details like “I had black coffee and apple pie with a slice of melted yellow cheese.” His diction is slangy and vernacular (not to mention casually racist and homophobic), where Rorschach tends toward theatrical, elevated words. Travis would never say something like, “This city is afraid of me. I have seen its true face.” When his diary entries become introspective, they tend to be vulnerable and searching, as opposed to Rorschach’s judgmental pronouncements. Travis reviles the city, sure, but he also explicitly laments his loneliness, something Rorschach only barely approaches when he asks (without a trace of irony), “Why are so few of us left active, healthy, and without personality disorders?”

However, just because Rorschach’s journal isn’t a “dead ringer” for Travis’s diary doesn’t mean that the comparison between Watchmen and Taxi Driver is pointless. On the contrary, I think it’s a very useful juxtaposition, one which illuminates them both.

THE NEW NOIR

Taxi Driver gets called a neo-noir film, a term which more or less means “a whole lot like film noir but made after 1958.” (See Hirsch and Schwartz, for example.) The notion of film noir itself has never enjoyed a stable, consensus definition, and in fact there is still contention over, for instance, whether it’s a style or a genre. But like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s relationship to pornography, critics know it when they see it.

Here are some film noir commonplaces:

- A mood of pessimism, cynicism, and/or fatalism

- Night scenes, especially night scenes in a city

- Rain. Lots and lots of rain.

- Also lots of smoke and smoking

- Femmes fatales. As Roger Ebert puts it, “Women who would just as soon kill you as love you, and vice versa.”

- An ordinary person drawn into crime, often based on some relationship with a femme fatale

- A grim investigator unraveling a crime, an investigation which often reveals deep corruption

- Odd or askew camera angles

- Shadowy or high-contrast visual composition

- Flashbacks, particularly telling the bulk of the movie in flashback, introduced by a frame story

- First-person voiceover narration

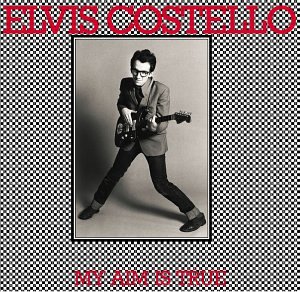

A movie doesn’t have to have all of these to be considered noir, but the more of them that occur in one movie, the more noir it becomes. Once I started thinking about Taxi Driver as a noir movie, it became blindingly obvious to me that Watchmen is a noir comic book, or at the very least that Rorschach is a noir character, right down to his 1940s trenchcoat and fedora. While his narration differs from that of Travis, the presence of their narration serves the same set of functions. It sets the grim tenor of the story but makes it clear that the mood is filtered through one character’s mind, and that this character is himself unreliable and twisted in certain aspects.

The juxtaposition of narration and images allows us sometimes to see the story’s world as the character sees it, and other times to understand through ironic contrast where the character’s perceptions are limited, or where he may be lying to himself or others. And as both Taxi Driver and Watchmen postdate the classic film noir period, they are fully aware of noir conventions and use voiceover as a kind of combination homage and allegiance.

They have plenty in common with the noir sensibility besides the voiceover, too. Both have an overall sinister tone, and both end with a psychopathic character unexpectedly cast in a heroic light. Both stalk the rainy night city, Travis in his cab and Rorschach on foot. Smoke, too, figures into each story in different ways. None of the characters in Taxi Driver smoke, but mist and steam emanates from the streets themselves — the first several shots in the film include a taxi emerging from a cloud of smoke (along with the title itself), and that same smoke following Travis as he walks into the cab service to apply for a job.

Lots of characters smoke in Watchmen. In just the first two chapters, we see Detective Fine, Hollis Mason, various criminals, restaurant patrons, Laurie Juspeczyk, and Eddie Blake smoking various types of cigarettes or cigars. In addition to his stogie, Blake also shoots riot gas to smoke up the streets, and makes Captain Metropolis’ map go up in smoke as well. However, the smokiest thing about the book is easily Rorschach’s dialogue balloons. The character is never seen with a cigarette, but every time he talks or thinks, the edges of his words crinkle and curl, an ever-present noir vapor.

Femmes fatales, on the other hand, are noticeably missing from both works. I’ve already discussed the role of women overall in Watchmen: they mainly exist to demonstrate or alter male emotional states. That is somewhat true for the classic femme fatale as well, but in Watchmen the women are more victims than masterminds. No woman is calling the shots on anything in that story, but rather stumbling or being thrown from one mishap to another. Even Janey Slater, clearly embittered and smoking up a storm, turns out to have been Adrian’s pawn in her takedown of Dr. Manhattan.

Women in Taxi Driver are filtered through Travis’s consciousness, which will only allow for two categories: virgin and whore. He can hardly bear either one. He idolizes what he sees as the purity and elevation of Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), and even manages to take her out on a date, only to make the site of their date a porno theater, as if he must taint that purity and expose the taintedness of his own inner self. Then he fixates upon a different mix of virgin and whore: the twelve-year-old prostitute Iris (Jodie Foster). Where he wanted to sully Betsy’s innocence, he wants to restore Iris’s, trying to convince her to go back home, and sending her $500 to help her leave her pimp Sport (Harvey Keitel). In neither case does he engage with the woman in question as a person, but rather interacts almost exclusively with his projections of them.

No, it isn’t a femme fatale who draws Travis into mass murder. Rather, it is his utter inability to connect with other human beings. Whether this disconnection is an aftereffect of service in Vietnam, or whether it is inherent to Travis himself, the film doesn’t make clear. However, his “loneliness has followed me all my life” voiceover suggests that while Vietnam may have stoked his inclination to violence, Travis’s fundamental alienation is his own.

De Niro does a masterful job of building upon screenwriter Paul Schrader’s script to demonstrate Travis’s utter lack of facility with simple personal interactions. He’s baffled by simple expressions like “moonlighting” or “how’s it hangin’?”. He’s culturally isolated — at various points he says he doesn’t know much about movies, much about music. He watches his television periodically, with a look of longing and confusion on his face; eventually he pushes that TV off its stand, destroying it. In a knowing twist on noir convention, Travis tries to kill the father figures of his various women, not at their urging, but as a sort of revenge for the relationships they have, which he is forever denied.

Watchmen takes the other noir plot — not the common man corrupted but the cynical detective whose astute investigations soon land him in trouble beyond his capacity to deal with. Moore begins the story as a standard murder mystery, and in fact for a moment we believe we might be following the police investigation of Eddie Blake’s death. Soon enough we are following Rorschach, but even then, the pattern of introducing a series of characters and providing background on the deceased is a familiar one to mystery readers. Watchmen turns out to have a lot more on its mind than just solving a crime, but at least from Rorschach’s point of view, his trajectory is not all that different from that of the classic Phillip Marlowe or J.J. Gittes type, the private eye whose own investigation devastates and undoes him.

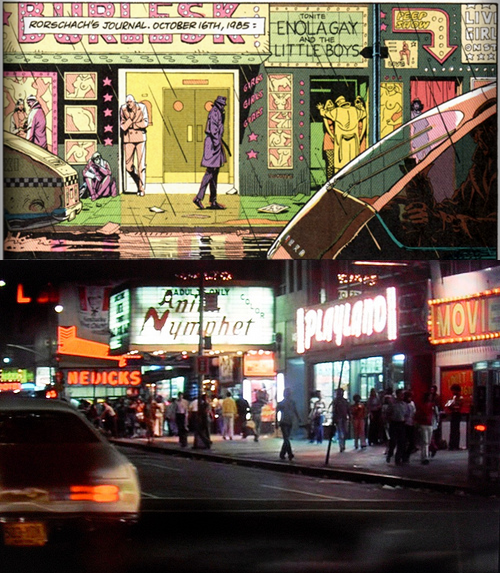

As for visual style, both Watchmen and Taxi Driver employ enough shadows and unsettling angles to easily qualify as neo-noir. Taxi Driver gives us shots of Travis’s eyes in the rear-view mirror, framed by blackness. It shows us fetishized close-ups of the taxi itself, driving through the rain, with garish Times Square movie marquees and porn store signs in the background. There’s a motif of high-angle shots straight down on a tableau – the personnel officer’s desk, the porn theater counter, the gun suitcase, Betsy’s desk. These culminate in a magnificent high-angle shot of the mass murder scene, moving slowly past the heads of stunned policemen, down the hallway and out into the street.

That same high angle appears in Watchmen‘s very first set of panels, the ones with the narration that started us down this road. The camera looks down at the bloodstained street, gradually pulling up, up, up to the site of Blake’s defenestration. Weird camera angles and shadowy composition abound especially (and not surprisingly) in the portions of Watchmen focused on Rorschach.

In Chapter 5, “Fearful Symmetry”, we get a recurring shot of the Rumrunner’s neon sign, reflected in a puddle, disturbed by Rorschach’s footstep. It’s a perfect noir shot, encompassing rain, darkness, the sinister city, and a sense of foreboding and destruction. Rorschach’s mask itself is the ultimate in high-contrast, its shadows always moving across his face. This effect is played up in “The Abyss Gazes Also”, whose penultimate panel is in fact nothing but blackness.

Finally, there are the flashbacks. Taxi Driver has none — it refuses to explain Travis by exploring his past, and it almost exclusively sticks to his point of view, denying us the capacity of understanding his world beyond his perception of it. Watchmen, on the other hand, is flashback-crazy. Whole chapters take us into the backstory of various characters, and previous chapters get called back by later chapters. Even single panels sometimes quickly throw us back to the past before returning to the scene at hand. Both, in their way, subvert the traditional noir mode of a frame story taking us into the past, either by sticking zenlike in the present or jumping around through time all the time.

Still, while neither Watchmen nor Taxi Driver ticks every box on the film noir checklist, there is more than enough evidence to call them both noir stories. But there’s something more: they’re also both superhero stories.

THE URBAN VIGILANTE

There are many ways to interpret the plot of Taxi Driver. Here’s one. An ordinary man, Travis Bickle, takes a blue-collar job after returning from war. This job brings him in contact with the worst parts of New York City. He sees firsthand the violence, the constant menace, the routine attacks upon innocent people, including attacks upon Travis himself. He witnesses the sleaze and degradation occurring in the city at night, and it becomes clear to him that the establishment police and politicians are fundamentally unable to stem its tide. He even connects with a heartbreaking victim of the city’s evil: a twelve-year-old girl named Iris, forced into prostitution by a pimp named Sport. That pimp pays Travis $20 to look the other way.

This $20 bill becomes a totem to Travis. He carries it with him, plagued by his guilt about not saving Iris from her dangerous situation. Finally, he makes up his mind to make a difference. “The idea had been growing in my brain for some time,” he writes in his diary. “True force.” He embarks on an intense regimen of physical training, honing his body until every muscle is tight, and he is nearly impervious to pain. He purchases an arsenal of weaponry, and rigs up ways to attach those weapons to his body, deploying them quickly when needed. He puts together a uniform which allows him to conceal the equipment he carries. “Here is a man who would not take it anymore,” he writes.

He uses the $20 bill to pay for Iris’ time, in a failed attempt to get her to leave Sport of her own volition. But he finally realizes: he is the one who must rescue her, and save the innocence of the city itself. He creates a new persona and guise, one which will strike fear into the hearts of those he hunts. At first, he tries to bring down the corrupt system by targeting a political demagogue, but he soon realizes that he must go into the underworld directly. Armed with his equipment and his frightening appearance, he defeats Sport and two of Sport’s henchmen. He returns Iris to her parents, and is hailed by them and by the media in general as a hero. Some time later, he has returned to his job in his ordinary identity, but we know that he is ready to confront evil again, whenever he encounters it.

Sounds an awful lot like a superhero origin story, doesn’t it? In a certain light, Travis doesn’t look so different from Bruce Wayne, or Tony Stark, or Frank Castle: men without superhuman powers, but who nonetheless deploy muscles, weapons, and a frightening appearance to fight the crime in their societies. For that matter, he’s even closer to a character like Rorschach, who shares all those qualities with Travis, and a few more as well.

Rorschach’s own origin story touches a lot of those same points. Walter Kovacs comes from a traumatic past and enters a blue-collar job. In the course of that job, he encounters a woman who later becomes the victim of a horrifying crime. Kovacs sees not only the ineffectiveness of standard social structures, but also the impassive detachment of people in general to the evil that surrounds them. He trains his body for strength and endurance, and acquires a set of equipment, a uniform, and a countenance to frighten the criminals he’s chosen to fight. He records his thoughts in a journal, in which he repeats his philosophy to himself. His culminating trip over the edge happens in response to the victimization of a child — his personality finds its fullest cohesion by murdering the victimizer.

Taxi Driver wasn’t meant to serve as a commentary on superhero stories, but it certainly was aware of its cinematic precursors, urban vigilante films like Dirty Harry, Walking Tall, and Death Wish. In those films, a man suffers tragedy and/or witnesses evil, and decides it’s time to work outside the law. He arms himself and slaughters the criminal(s) responsible.

The difference is that in the preceding films, the vigilante is lionized and held as the moral center, in contrast to corrupt or incompetent law enforcement. Schrader applies a corrective to this narrative with Taxi Driver, showing us that the man who kills criminals is himself violently disturbed. In fact, in Taxi Driver Travis simply wants to kill the father figure to one of his women, and tries first to kill the presidential candidate. It’s only because he fails, and ends up killing the pimp, that he is hailed as a hero. Watchmen, too, deeply problematizes the notion of vigilante heroism, in response to a similar romanticization of it in superhero comics. It shows Rorschach, like Travis, to be a deeply lonely man, one who has become insane and dangerous based on his experiences and his disconnection.

Travis Bickle does not understand other human beings. He sees them as objects — threats, idols, barriers. His movies are porn movies, whose entire job is to turn people into objects. Porn lets you project yourself, explicitly, into a sexual interaction. It’s the closest Travis comes to a connection. Rorschach, too, does not relate to other people, and tends to see them as objects, pawns on a board. Moreover, the traditional superhero genre has a hard time understanding human beings as well. It objectifies them into projection screen, threat, barrier, or prize. Watchmen surrounds Rorschach with humans, rather than objects, and by doing so reveals the absurdity of his Objectivism.

Film noir was never concerned with heroism. Its subject was the darker sides of humanity, and how the naive man can be inadvertently drawn into them. Both the urban vigilante film and the superhero genre, however, take heroism as a central theme and trope. By mixing noir into these genres, Taxi Driver and Watchmen leave us questioning those tropes, and understanding that sometimes our cultural perception of good is no more valid than our perception of evil. Travis Bickle looks in the mirror and says, “You talkin’ to me?” But he’s only talking to himself. It’s Scorsese, Schrader, Moore, and Gibbons who are talking to us.

Next Entry: Comin’ For To Carry Me Home

Previous Entry: The Superhuman Crew