“To me, when we talk about the world, we are talking about our ideas of the world. Our ideas of organisation, our different religions, our different economic systems, our ideas about it are the world. We are heading for a radical revision where you could say we are heading towards the end of the world, but more in the R.E.M. sense than the Revelation sense. That’s what apocalypse means — revelation. I could square that with the end of the world, a revelation, a new way of looking at things, something that completely radicalises our notions of the where we were, when we were, what we were, something like that would constitute an end to the world in the kind of abstract, yet very real, sense — that I am talking about. A change in the language, a change in the thinking, a change in the music. It wouldn’t take much — one big scientific idea, or artistic idea, one good book, one good painting — who knows?” — Alan Moore, 1998

Today’s topic, friends, is the end of the world. I say unto thee: behold and beware, for I bring you multitudes of Watchmen spoilers. Also, I suppose, Bible spoilers? Can the Bible be spoiled? Besides via misinterpretation, I mean? 🙂

The Christian holy book is at issue today because of an observation made by the Annotated Watchmen, v2.0, about page 24 of chapter 1:

The band name, “Pale Horse,” refers to Revelations [sic] 6:8, where the fourth horseman of the Apocalypse, Death, is said to ride a pale horse.

(The words “Pale Horse” are partially obscured in this panel, as frequently happens in Watchmen, but they show up plenty of other places, such as emblazoned above the dead bodies in Chapter 12.)

So, in quite a tonal switch from reading DC and Charlton comics, I read the Bible. Well, the last book of it anyway.

It makes sense that Watchmen would refer to Revelation. They are both stories of apocalypse, and not in the R.E.M. sense either. The modern meaning of “apocalypse” relates to catastrophic destruction, irrevocable change, the end of the world. But etymologically, “apocalypse” derives from Greek, meaning “uncover” or “reveal.” The book of Revelation encompasses both senses of the word. It describes destruction on an epic scale, with God visiting one catastrophe after another upon humanity — the earth quakes, the waters turn to blood, meteors fall and set the forests ablaze. Locusts with human faces and scorpions’ tails boil from a bottomless pit, slaughtering people alongside avenging angels, amid fire, darkness, starvation, drought, hailstones, and disease. These themes repeat throughout the book, starting with the four horsemen representing conquest, war, famine, and death. At the same time, Revelation is, well, a revelation, partly because it was revealed in a vision to its writer, John of Patmos, and partly because it demonstrates the final judgment of God, the creation of the New Jerusalem, and the vindication of Christian believers, who are of course separated from the Earth before all those horrible things happen to it.

Watchmen certainly includes the horror; Moore and Gibbons devote six splash pages in a row to making sure we know it as Chapter 12 opens. However, in the first of many inversions of the Biblical model, Veidt’s apocalypse is explicitly antithetical to revelation, demanding instead that everyone to whom it is revealed either keep it secret or be destroyed to preserve the secret. Revelation 12:9 refers to Satan as “the deceiver of the whole world”, and describes how he is defeated and thrown down to earth by the archangel Michael. The book equates deception with evil, and describes Jesus as bringing a fierce and disturbing truth — it refers no less than five times to a sword coming from Jesus’ mouth. Salvation of the world depends on this truth, and on the overthrow of Satan the deceiver.

In Watchmen, though, Veidt is the deceiver of the world, and in his mind at least, he deceives the world in order to save it. “Unable to unite the world by conquest…” says Veidt, “I would trick it: frighten it towards salvation with history’s greatest practical joke.” The sword comes not from Adrian’s mouth, but from somewhere altogether more hidden and secret — the bottom of the world. Not only that, he makes the other characters complicit in his secret, asking “Will you expose me, undoing the peace millions died for? …Morally, you’re in checkmate.” And the other characters agree, all except for Rorschach, who meets his own personal apocalypse at the hands of the book’s most godlike character. Where Revelation shows war in heaven, Watchmen‘s pantheon reluctantly unites, after destroying its lone dissenting vote.

Rorschach himself is the book’s prime exemplar of the moral sense on display in Revelation. In many parts of the New Testament, Jesus’s teachings complicate and problematize the old vengeful approach of the Old Testament God. Take for example, this excerpt from the Sermon on the Mount, in Matthew 5:38-42

“You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if anyone would sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well. And if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. Give to the one who begs from you, and do not refuse the one who would borrow from you.”

(All my Bible quotes are from the English Standard Version, BTW and FWIW.) But in Revelation, no cheeks are turned. The book couldn’t be more dualistic. God and Jesus stand on one side, Satan and his beasts on the other. Babylon the whore stands on one side, New Jerusalem the bride on the other. The 144,000 of Israel, along with a “great multitude” of the faithful from every nation are preserved in heaven, while the rest of humanity is condemned to round after round of torture and disaster. No Limbo, no Purgatory. Nobody gets just a mild punishment. Nobody even repents, despite what you’d have to think are some pretty convincing reasons to give it a shot:

The rest of mankind, who were not killed by these plagues, did not repent of the works of their hands nor give up worshiping demons and idols of gold and silver and bronze and stone and wood, which cannot see or hear or walk, nor did they repent of their murders or their sorceries or their sexual immorality or their thefts. (Revelation 9:20-21)

(John of Patmos really loved lists.)

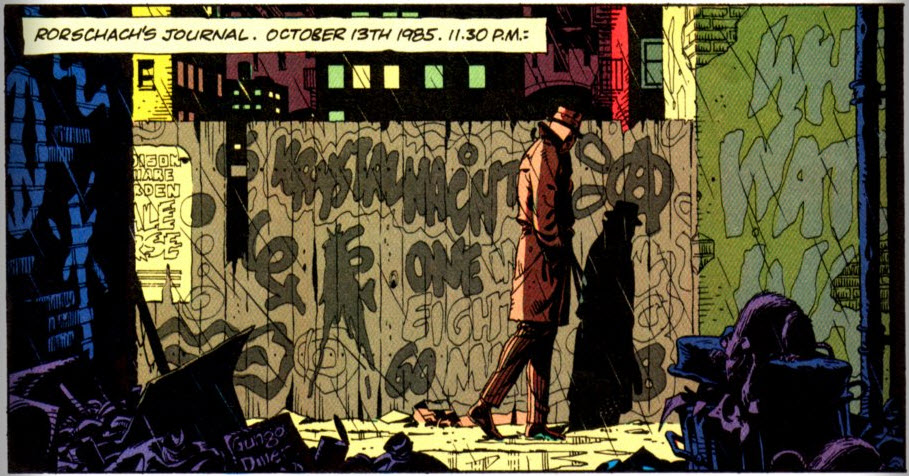

In other words, as Rorschach’s journal tells us just a few panels down from the first Pale Horse reference:

(The word “Armageddon” itself comes from Revelation too — it’s the gathering place of the armies of evil in preparation for their final battle: “And they assembled them at the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon.” (Rev 16:16))

In fact, Rorschach’s journal has another connection to Revelation, in which God several times makes the point, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end.” (Rev 21:6) So if God is the Alpha and Omega of Revelation, what is the Alpha and Omega of Watchmen? Why, it’s Rorschach’s journal. Chapter 1, page 1, panel 1, at the very top of the panel, reads: “Rorschach’s Journal. October 12th, 1985”. Then, at the very bottom of the final page of the final chapter is an image of Rorschach’s journal. In between the word and the image lies the full comic, the rest of the world. Watchmen‘s world leads us to wonder: what if God were like Dr. Manhattan? But Revelation presents a God who is much more like Rorschach, preserving the innocent and casting all the rest into a lake of fire.

Watchmen itself is an inversion of Revelation — all flawed humans and shades of grey, which contrasts so well with Rorschach’s dualism and the usual Good vs. Evil conflicts previously inherent to the superhero genre. In fact, one could argue that both Revelation and the general thrust of the superhero genre are expressions of the ancient combat myth pattern, which follows a familiar trajectory. Biblical scholar Adela Yarbro Collins, who has thoroughly made the case for Revelation’s connection to combat myth, maps out this trajectory:

A rebellion, usually led by a dragon or other beast, threatens the reigning gods, or the king of the gods. Sometimes the ruling god is defeated, even killed, and then the dragon reigns in chaos for a time. Finally the beast is defeated by the god who ruled before, or some ally of his. Following his victory the reestablished king of the gods (or a new, young king in his stead) builds his house or temple, marries and produces offspring, or hosts a great banquet. These latter elements represent the reestablishment of order and fertility. (Crisis And Catharsis: The Power Of The Apocalypse, pg. 148)

Now, superhero stories don’t tend to be festooned with dragons, Fin Fang Foom aside. But if the dragon in ancient tales stood in for a force too overwhelming for ordinary humans to fight, then supervillains fill that role nicely. They threaten to overthrow whoever’s name is on the cover of the book, or that hero’s home city, country, planet, or galaxy. A mighty battle is joined, and the hero or team often is defeated or nearly defeated, before coming back and defeating the villain, restoring order. Due to the serial nature of the comics, we tend to skip over the final portion, since we understand that restoration of order is only temporary until the next issue arrives. Still, the X-Mansion gets rebuilt again and again, the Fantastic Four affirm or restore the safety of their children, and the Justice League shares convivial bonhomie at the beginnings and/or endings of its stories.

No such celebration happens in Watchmen, because the dragon is not defeated. Veidt carries out his plot and succeeds. He does not reign in chaos, but creates a fragile order based on deception. Moore upends the familiar and comforting story arc we’ve come to expect, and asks us whether we really wanted that story anyway. He shows us gods whose reign brought fear and uncertainty to their kingdoms, and were deposed (with varying degrees of success) by their subjects. But in their absence, the world finds still more chaos, brought about by ordinary human avarice, venality, and lust for power — no dragon necessary.

Indeed, Veidt sees himself as the king of the gods, and from his point of view the story does follow the combat myth pattern — he even throws a party for his scientists… as a means of killing them. He believes himself to have built a New Jerusalem of the world, but several signs point to his fallibility, the great distance between himself and the God of Revelation. Watchmen‘s most godlike figure questions the worth of Veidt’s plan, and the final scene intimates that the house of cards will tumble. Even Dan and Laurie gesture at fertility in the denouement (Dan’s comment, “Y’know, maybe that wasn’t such a bad idea of your mother’s…”), but immediately turn away. (“Children? Forget it.”)

In her study of the psychological power of apocalyptic tales, Yarbro Collins tells us, “The task of Revelation was to overcome the unbearable tension perceived by the author between what was and what ought to have been.” (Ibid, p. 141) Ozymandias authors his apocalypse for the same purpose, hoping to finally prove to the Comedian in his head that he wouldn’t just be “the smartest man on the cinder.” The artificial space squid’s appearance at the Pale Horse concert associates Veidt’s plan with Revelation’s fourth horseman of the apocalypse, and let’s not forget that John of Patmos saw those horsemen as a good thing, since the faithful would be spared from their destruction. John’s apocalypse never came, and Adrian’s is a pale shadow of it, because contrary to his apparent beliefs, Ozymandias is no savior, and certainly no god.

Next Entry: Let’s See Action

Previous Entry: Across The Universes

Leave a Reply