In the previous installment, we looked at some of the Charlton “Action Heroes” created or co-created by Steve Ditko, upon whom the Watchmen characters were based: Captain Atom, Nightshade, Blue Beetle, and The Question. However, there were a number of O.P.C. as well — Other People’s Characters. They too had their Watchmen equivalents, so watch out for Watchmen spoilers as we round out the Charlton stable.

Judomaster

First, however, there is one action hero who did not have a Watchmen counterpart: the Frank McLaughlin character Judomaster. Rip Jagger is an Army sergeant in 1943, fighting the Japanese on an unnamed South Pacific island, when one of his trigger-happy privates shoots an unarmed girl. Jagger rescues the girl, but is pinned down by enemy fire. Suddenly, kendo-wielding natives ambush the Japanese soldiers, then knock Jagger unconscious. He awakens in a cave, where an ancient sensei thanks Jagger for rescuing (what turns out to be) the sensei’s granddaughter, but tells him that the rest of his unit is dead. Having nowhere else to go, Jagger trains under the sensei to learn judo, becoming so good that he achieves a black belt. Joining forces with the natives to fight the Japanese, Jagger dons the symbolic identity of Judomaster, whose uniform includes a samurai-esque high ponytail and a yellow-on-red rising sun flag motif.

That was the origin as told in Special War Series #4, a comic which was immediately discontinued. Judomaster reappeared the next month as a backup feature in Sarge Steel (who we’ll discuss below), and then a few months later got his own series. In that series, he joins back up with the Army, fights a variety of martial-arts-themed villains, and even picks up a sidekick called Tiger, who you may recall would later on become Nightshade’s trainer.

The theme of Judomaster’s stories was, well, judo. McLaughlin was quite a judo enthusiast, having trained since age 18 and even taught judo classes at the local YMCA. Even before he created Judomaster, he was drawing judo instruction backup features for Sarge Steel, panel after panel patiently explaining complicated throws and always ending with an admonition to be safe and work with an instructor. Those features continued into Judomaster, blurbed with cover copy like “SPECIAL BONUS: Judomaster’s defense against a bully… see how… step by step!” Similarly, Judomaster’s stories make an ongoing effort to teach judo principles and terminology. A typical piece of dialogue: “Judo is developed in three phases. Renshindo is physical development — shoubuho develops proficiency in combat and shushinho results in mental development! We work at these three things here in the dojo, our room where we meet for lectures and practice!”

Between its didactic focus and its WWII setting, there isn’t much here that would adapt easily into the Watchmen milieu, so this is one action hero who doesn’t make the leap into Moore’s world. However, there are some elements that arguably come across nevertheless. First, because of its setting in the previous generation, Judomaster serves as a prelude to the rest of the action heroes, just as the Minutemen set the stage for the Watchmen. Similar to Captain America’s juxtaposition against the 1960s Marvel universe, Judomaster appears in a world where there is no ambiguity, where the enemies are always clear. Also like Captain America, Judomaster fought a skull-faced Nazi, this one called the Smiling Skull. That name hearkens pretty clearly to the Screaming Skull, who Hollis Mason mentions running into at the grocery store. So although Watchmen didn’t inherit Judomaster, it may have (just slightly) inherited one of his villains.

Sarge Steel

Before Judomaster, the guy giving out judo advice in the backs of Charlton comics was a tough private eye named Sarge Steel. However, unlike Judomaster, Steel wasn’t created by McLaughlin but rather by Pat Masulli, the guy who initially hired McLaughlin at Charlton. In true “Captain Adam” fashion, the character’s real name is… Sargent Steel. He was also an Army sergeant, just to cover all the bases. During a Vietnam tour of duty, he makes an enemy of Chinese terrorist Ivan Chung, which results in a series of attempts on Steel’s life. While Steel is on R&R furlough in Saigon, a grenade is thrown at his feet. He tries to throw it out the window, but it’s been covered in glue, and it destroys his hand. For some reason, the Army doctors replace the missing hand with a clenched steel fist. What the science of prosthetics has gained in function, it has surely lost in badassery.

After the glued grenade ends his Army career, Steel becomes a private detective, and later a CIA agent who maintains a cover as a private detective. His stories are pretty much Chandler/Hammett pastiches, albeit with a bunch of spy stuff rather than seedy California underworld characters. The cliches pile up thick and fast, as do the cars and bodies. Femmes fatale are everywhere, as are initially tough female allies who inevitably crumble into damsel-in-distress mode so that Sarge can save them. The steel fist becomes a prominent feature in every Sarge Steel story. It can deflect bullets, knock out angry animals, break through doorways, and other amazing feats. It’s a rather, uh, hamfisted symbol for Steel’s primary quality, and in fact the predominant theme of his stories: toughness. In fact, Steel is occasionally billed as “The Toughest Man In The World!”, and panel after hardboiled panel tries to prove the point.

The annotations say that “the Comedian shares some attributes with Sarge Steel,” and it’s easy to see what they mean. In his way, Edward Blake tries to live out the agent/detective’s hardheaded, womanizing image. As he says to Moloch, “The world was tough, you just hadda be tougher, right?” Only unlike Sarge Steel, The Comedian’s toughness didn’t win him any happy endings, and it didn’t protect him from much either. He says the line above while weeping inconsolably in front of his longtime enemy, his face is disfigured by the results of his own evil, and he doesn’t even survive to page one of the story. As for his attempts at womanizing, they get him publicly excoriated as a rapist, and alienate him permanently from his only daughter. So much for toughness.

The Peacemaker

Though he’s got plenty of Sarge Steel in his personality, the Comedian is said to be patterned primarily after The Peacemaker. This is a character created by Joe Gill and Pat Boyette, who originally appeared as a backup feature in a war/espionage comic called Fightin’ 5. In his civilian identity, he’s diplomat Christopher Smith, who travels around the world with his efforts to advance the cause of peace through détente and negotiation. However, when negotiations break down or prove futile, he breaks out a helmet, uniform, and panoply of technology to become The Peacemaker, a dude who punches people and blows stuff up. The first panel of his origin sets out the notion: “This is a man who detests war, violence, and the dreadful waste of human life in senseless conflicts between nations… a man who loves peace… so much so, that he is willing to fight for it!!”

You’d think that this would have to be a short-lived gimmick. Of course, as it turned out, the entire Action Heroes line was short-lived, but one wonders just how many issues Christopher Smith could have continued failing at his job so that he could assume his other identity. As Alan Moore says in a 2000 interview, “I could see the holes in that one straightaway.” DC must have seen them too, because after they acquired the character, they retconned his contradictory philosophy as a mental illness caused by having a Nazi death camp commandant for a father. Thus, although the ostensible theme of Peacemaker stories is peace, I’d suggest that their most prominent attribute is in fact contradiction.

It’s easy to see how The Comedian takes after Sarge Steel. His relation to The Peacemaker isn’t so clear. The Comedian certainly doesn’t love peace, though he’s gung-ho about the fighting part. He’s not a genius who designed a bunch of weapons. Lord knows he’s no diplomat. So in just what way does he take after the Peacemaker?

I suppose the biggest similarity between the characters is in their internal contradictions. The Peacemaker is a supposed pacifist who spends most of each story attacking people. The Comedian is a supposed hero whose scenes mostly involve rape, murder, mayhem, tear-gassing civilians, and so forth. While I don’t think the Peacemaker was intended as any sort of ironic critique on national foreign policy, The Comedian is certainly written with an eye towards the absurdity of enforcing world peace (or any other kind of peace) through brutality and force. The idea of taking a guy like Blake and sending him out to pacify riots, end wars, or clean up crime… well, all anybody can do is laugh.

Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt

The final figure in our O.P.C. lineup is a fellow named Peter Cannon, written and drawn by the enigmatic P.A.M. Charlton stated that it was not at liberty to disclose P.A.M.’s identity, and letter columns were full of speculation about it. The closest the company would come would be to occasionally shoot down a reader’s theory. In the end, P.A.M. turned out to be Peter A. Morisi, who did indeed have an interest in keeping his identity secret — his day job was as a New York City policeman, and he was worried that he’d be fired if his moonlighting was discovered. It’s a rather superheroic conundrum really, except that the crimefighter is the true identity while the mysterious pseudonym belongs to the struggling artist. His character’s situation, though, was a bit different.

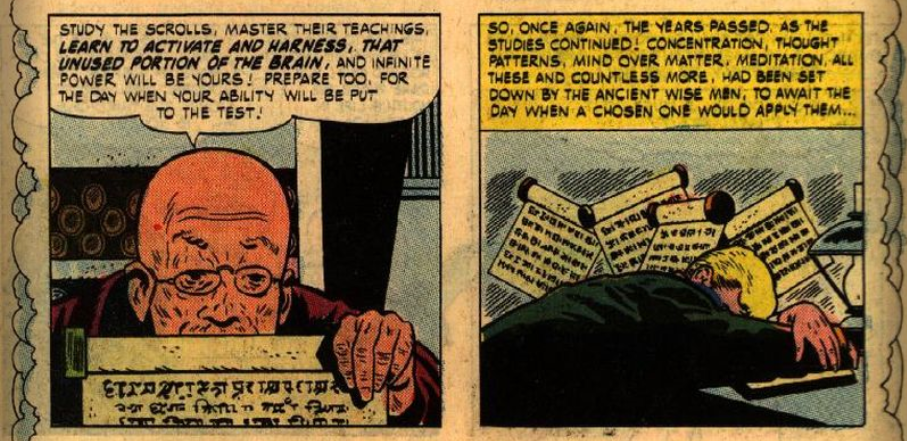

When Peter Cannon was just an infant, his parents brought him to a secluded lamasery in the Himalayas. Dr. Richard and Mary Cannon were a medical team fighting an outbreak of black plague in the area. They succeeded in conquering the disease, but it claimed them as its final victims. In gratitude for their sacrifice, the “high abbot” promises not only to raise Peter, but to “develop within the child, the highest degree of mental and physical perfection! Then, we will entrust unto him, the knowledge of the ancient scrolls.” This draws objections from “The Hooded One” who until Peter’s arrival had been slated to receive that knowledge. (Apparently, There Can Be Only One.)

With both mentor and archenemy thus in place, Peter set out on his training, which was a bunch of exercise and education, combined with “the mysteries and power of the mind!” See, what the ancient scrolls teach is the old saw that “Man is capable of all things, but lacks the strength of will to attain his potential, for he uses but one tenth of his brain, throughout his lifetime!” (Despite having been thoroughly debunked for ages, this myth is such a compelling origin for superpowers that it’s still getting used today.) Thus Peter is taught “concentration, thought patterns, mind over matter, meditation,” and so forth, until he emerges as a hyper-capable hero.

He’s as physically fit as a person can be, but not superhumanly so. He’s very well-educated, but he doesn’t present himself as a polymath. No, his superpower, as well as the primary theme of his stories, is willpower. The “high abbot”1 posits “strength of will” as the reason why 90% of the brain remains unused, so it is through strength of will that Peter accesses his abilities. He even has a catchphrase for when he’s about to do something awesome: “I can do it… I must do it… I will do it!”

After passing the final tests that complete his training, Peter is sent from the lamasery into our world, accompanied by his childhood friend and assistant Tabu. He’s rather disappointed in what he finds — the sometimes squalid and venal world is no match for the monastic culture that raised him. Consequently, he becomes a rather reluctant hero. In pretty much every issue, Tabu has to wheedle and cajole Peter into donning his Thunderbolt costume and going out to save the day. A typical exchange:

TABU: Can you forever deny the benefits of your power of will to this society in which we live?

PETER: Uh-huh! As long as civilization deals in greed, hatred, and violence, I want no part of it!

Cannon prefers to keep to himself, training and studying, but inevitably there is always some situation that forces him into action. Or at least, there was for about 10 issues, after which he was gone along with the rest of the Action Heroes.

Adrian Veidt’s parents were no medical saviors — all we know about them is his description: “intellectually unremarkable, possessing no obvious genetic advantages.” He grew up not in isolation but luxury, here in the world with the rest of us, eventually orphaned like Peter Cannon but not until he was 17. His intake of Asian wisdom was limited to a ball of hashish he procured in Tibet. (Thunderbolt’s true successor in the Eastern philosophy department may in fact be Denny O’Neil’s version of The Question, but more about that next time.) Thus there was no guru and no ancient scrolls — his only teachings were the promptings of his own intellect and ego.

We only have his word for all of this, and he may not be exactly reliable, what with being the villain of the piece and all. He deludes himself in some important and visible ways, which means that his account of his life may be questionable as well. So, he may not actually be the smartest person in the world, though at the very least, we have to admit that he’s a hell of a planner. And like Peter Cannon, he has considerable contempt for the world he means to save. While he speaks of “humanity’s salvation,” he sees it in terms as abstract as a math problem, and doesn’t hesitate to kill millions of people, even as he may claim to have made himself feel every death. It’s as if his left brain, the analytic and logical side, is in complete control, to the exclusion of the feeling & compassionate right brain. Thunderbolt may use 100% of his brain, but Ozymandias looks like he’s running right around 50%.

So while Veidt2 is certainly no dummy, he seems to lack any wisdom to match his exceptional intelligence. What he clearly does have in abundance, though, is willpower. Through his own desire to do so, he perfects his body and reflexes, so much so that he can even catch a bullet. He amasses a personal fortune well beyond his inheritance, through his scientific successes and business acumen. And as he gazes at the half-burned map in the abortive Crimebusters meeting, one can almost see the thoughts forming in his head: I can do it… I must do it… I will do it.

Final Thoughts

Thus concludes our trip through the Charlton inspirations for Watchmen characters. What I think becomes clear is that although Moore worried that his superhero murder mystery wouldn’t work without established characters, Watchmen is actually a much better book for the freedom it has from established continuity. In nearly every case, Moore’s changes to the characters made them deeper and more intriguing, and he was also able to entirely eliminate or amalgamate characters as he saw fit, thereby eliding the woolliness and baggage that tends to accompany existing characters.

Watchmen is a jewel in so many ways — Moore and Gibbons are just so perfectly in control, and one aspect of this is that Moore got to decide exactly what everybody’s past was, and didn’t have to engage with messes like The Question’s Objectivism or The Blue Beetle’s tangled history. He could write Under The Hood in a viewpoint that worked perfectly for the story, rather than one that would have to be wrenched in there from established continuity. And he could tap into the keystone theme of each character and ring changes upon it in ways that resonated with each other.

Of course, that’s not to say that Alan Moore isn’t adept with O.P.C. While nearly every generalization about his work falls apart in the face of his astonishing prolificity, I think it’s safe to say that he’s very good at engaging with other people’s characters and revealing startling new depths in them. From Miracleman to Swamp Thing to Batman & Superman to the dizzying array of literary characters in the League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen series, and even the historical characters on display in From Hell or the eroticized rewrites of Lost Girls, Moore can reveal fresh angles on established figures, with deftness and economy. No doubt the book would still have been great if he’d been given free rein over the Charlton characters.

The fact that he wasn’t, though, means that we got not only reinterpretations but entirely new creations, while the Charlton characters were allowed to continue growing and evolving in the DC Universe, free of the Armageddon that ends Watchmen. In fact, in one instance a Charlton character even got to react to Moore’s version of himself, even as he had already become someone quite different from his origins. That’s where we’ll pick up next time.

Next Entry: In The Form Of A Question

Previous Entry: Ditko Fever

Endnotes

1 I have to scare-quote “high abbot”, because whoever heard of an abbot running a lamasery? It would be like a lama running an abbey![Back to post]

2 In my comic-book-history research, I stumbled across something interesting about this name. In 1928, an actor named Conrad Veidt had the title role in a film called “The Man Who Laughs”, based on a Victor Hugo novel about a noble scion who has face carved into a permanent grin. According to Patrick Day of the L.A. Times, “Stills of Veidt were used as inspiration by the Joker’s creators, artist Bob Kane, writer Bill Finger and artist Jerry Robinson.” Moore’s definitive Joker story, Batman: The Killing Joke, appeared shortly after Watchmen. Since we know that Moore is a guy who does his research, could he have drawn inspiration for the name of Watchmen‘s villain from the inspiration for one of the greatest villains in all of comics?[Back to post]

Leave a Reply