In the last two entries, I superverbosely examined all the various Charlton “Action Heroes” upon whom the Watchmen characters are based, and noted that Alan Moore had to create his own characters because although DC had acquired the Charlton heroes, DC editor-in-chief (and former Charlton executive editor) Dick Giordano wanted to integrate them into the DC universe rather than, y’know, corrupting and killing them.

So Watchmen got new characters while some of the Charlton characters found their way into various inhabited quarters. Captain Atom got his own series, Blue Beetle landed in the Justice League, and Nightshade joined the Suicide Squad.

Then there was The Question. Unlike those other, more generic superheroes, who could be slotted pretty easily into an ongoing comic universe, The Question was a bit of an oddball. He didn’t have a costume, really (besides the lack of a face), and he didn’t have any superpowers. Most importantly, his strident Objectivism was a deeply idiosyncratic Steve Ditko expression, one that stood pretty much alone in the mainstream comics world. How could anybody who wasn’t Ditko keep writing a character like this?1

The writer DC chose for the job was Denny O’Neil, and the choice made it clear that The Question would be changing. (And this is probably a good time to note that spoilers follow for Watchmen and O’Neil’s Question series.) Like Ditko and Giordano, O’Neil was another Charlton veteran who arrived to shake up the rather stodgy and stale DC stable in 1968. He really made his name a couple of years later, with a brief but legendary run on Green Lantern, which became Green Lantern/Green Arrow under his watch. In that series, O’Neil teamed with artist Neal Adams to bring a street-level realism to the formerly rather cosmic and abstract Green Lantern tales. Suddenly, the prototypical DC hero, a rather bland and one-dimensional “big brave uncle”, was forced to confront situations in which the law wasn’t always on the side of the righteous, and social inequity loomed larger than supervillainous plots.

Green Arrow was introduced as a fiery progressive foil to Lantern’s true blue Establishment values, but O’Neil wisely avoided blatant partisanship by keeping both heroes heroic and flawed. Arrow in his way is as shrill and didactic a voice for liberalism as The Question ever was for conservatism, and sometimes Green Lantern’s cautiousness saved Arrow from making crucial mistakes, even as Arrow opened Lantern’s eyes to a raft of problems he’d never noticed or cared about before.

The book took on racism, slumlords, cults, corporate oppression, and even heroin addiction, in a story that followed immediately on the heels of Stan Lee’s Comics Code-breaking anti-drug story in Spider-Man. Evenhanded though O’Neil was, the book’s depiction of these issues make it pretty clear that his sympathies are on the left. In one of its most famous and repeated passages, an elderly black man angrily confronts Green Lantern, saying, “I been readin’ about you… how you work for the blue skins… and how on a planet someplace you helped out the orange skins… and you done considerable for the purple skins! Only there’s skins you never bothered with–! …The black skins! I want to know… how come?! Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern!” And Mr. Green Lantern has no answer, just a feeble, “I… can’t.”

So how would perhaps the most famously liberal writer in comicdom do justice to the famously Randian Question? Well, the first thing O’Neil did to the character was to kill him. Issue 12, page 1 of O’Neil’s Question series begins with the caption, “Hub City, Friday, November 21, 10:45 P.M.: Charles Victor Szasz has exactly 25 hours and 15 minutes to live.” But wait, what does that have to do with The Question, whose name is Vic Sage? Well, it seems O’Neil applied a bit of retcon to Ditko’s character, declaring that “Vic Sage” is in fact only a pseudonym for an orphan born Charles Victor Szasz. He kept Sage’s television career, his relationship with professor Aristotle Rodor (who he calls “Tot”), and his violent investigative techniques as The Question, but applied a hardboiled noir filter and drained out Ditko’s unsubtle philosophical and political commentary.

True to its word, that first issue’s last panel shows Vic Sage, aka Charles Victor Szasz, lying at the bottom of a river for at least ten minutes after being beaten lifeless and then shot in the head, his Question mask floating slowly upward. He was defeated by a martial arts expert named Lady Shiva, and then abused and pummeled by various generic punks before being shot with an air gun, the slug traveling all the way through his head. Aforementioned punks then dumped him in a river. Hardly an auspicious beginning for a hero’s new series! In fact, it reads more like a series-ending story.

And in fact, that’s what it was. Oh, the character came back, miraculously3 nursed back to health by that selfsame Lady Shiva, for reasons of her own. But Ditko’s version of Vic Sage was dead forever, to be reborn as someone quite different. After reviving him, Lady Shiva took Sage to her mentor Richard Dragon (a character created by O’Neil in a novel and later transferred to the DC universe.) Spending a year with Dragon, Sage discards his old self to adopt Zen philosophy and meditation. In fact, the book embraces Zen and Eastern philosophy so enthusiastically that O’Neil not only dramatizes various koans throughout the run, he also provides a “Recommended Reading” text at the end of each issue, encompassing titles like Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance, The Wandering Taoist, and The Art Of War.

O’Neil also revamps The Question’s driving passion. In the Ditko stories, that passion is pretty clearly for the capital-T Truth, which naturally in Ditko’s viewpoint exists as objective fact, waiting only to be announced by that hero noble and unafraid enough to tell it. According to O’Neil, The Question’s passion is in fact… curiosity. Where Superman has altruism, Batman has revenge, and Spider-Man has guilt, O’Neil’s Question just has a burning desire to know things. As superhero obsessions go, it’s certainly different, but not very propulsive. “Gee, I’d like to know more about that” isn’t exactly bursting with narrative tension.

To compensate, O’Neil places his hero in Hub City, which he depicts as the very archetype of urban decay. Unlike Marvel, which generally sets its superheroes in real locations, DC tends to set its stories in fictional metropolises such as, well, Metropolis. Then there’s Gotham City, Coast City, Central City, Star City… you get the picture. Usually this approach leaves the stories feeling more abstract, less grounded, and a touch sillier. In the case of Hub City, however, the distancing tactic worked to the stories’ advantage. Because he wasn’t naming real names, O’Neil was free to make Hub City the worst city in America — corrupt cops, rampant crime, drugs everywhere, government incompetent and/or corrupt, orphanages bankrupt, and so on. If O’Neil had explicitly set his Question stories in East St. Louis, Illinois (upon which he based Hub City), he’d surely have endured angry letters and maybe even legal trouble. But with “Hub City”, he was free to portray the blight we know exists without the discomfort of disparaging someone’s actual home.

The fact that The Question lived in Hub City forced him into dramatic situations that curiosity alone could not have produced, while at the same time pushing O’Neil’s social justice themes to the fore. Supervillains were rather thin on the ground in Hub City, but human misery was everywhere Vic Sage looked. That misery drove most of his stories, in one fashion or another. Vic may be curious, but in Hub City, all his questions had tragic answers.

Predictably, Objectivist fans of the Ditko character freaked out at these changes, writing in to tell O’Neil that his storyline amounted to a cult brainwashing, but the die was cast. Or, at least, mostly. Vic never came off like a junior Ayn Rand again, but neither did he settle in Zen calm. In Hub City, how could he? He struggles constantly with feelings of anger, bitterness, and helplessness, falling further and further away from his meditation practice as the series goes on. One of these “behavioral dips” impels the story that brings you today’s entry. For as the annotations tell us:

The connection to the Charlton Comics heroes was recognized by the writers that carried on those heroes. In a late 1980s issue of The Question, the Question reads a copy of Watchmen and tries to emulate Rorschach’s methods.

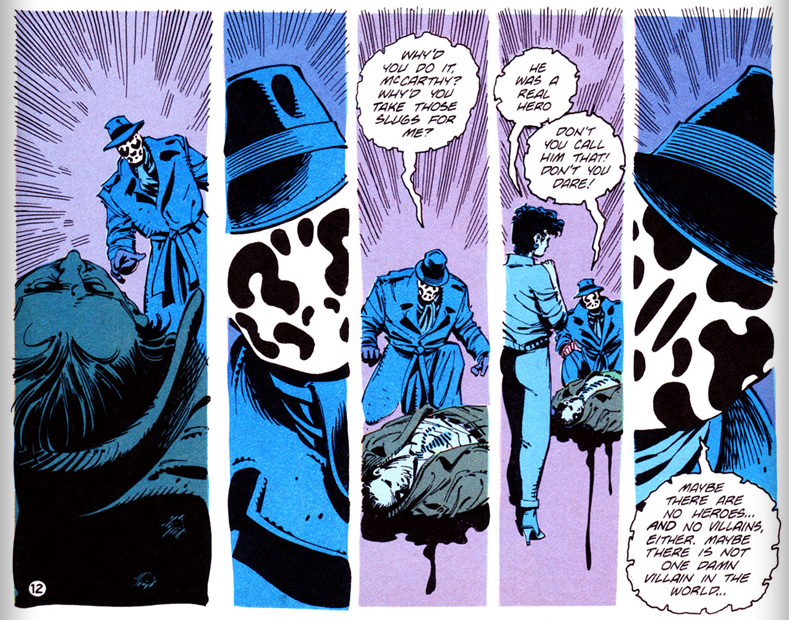

The issue in question is #17. Things haven’t been going particularly well for Vic. In issue #15, he meets a hardcore racist named Loomis McCarthy, whom he despises. Then that selfsame McCarthy takes a bullet meant for Vic, sacrificing his own life even as Vic was in the midst of telling him, “I loathe you and everything about you — and everything you stand for.” Vic gets furious at a bystander who calls McCarthy a hero:

Then in #16, there’s an assassination attempt on the Hub City chief of police, who is seemingly the only honest cop in the whole burg. (At least, he’s the only one with a name.) At the end of the issue, The Question apprehends the assailant, who goes by the handle “Sundance.” As #17 begins, the imprisoned Sundance has summoned a fancy lawyer from Seattle.4 Vic is there in a journalistic capacity as the lawyer arrives, and thus witnesses the twist: the lawyer isn’t a lawyer at all, but rather the assassin’s partner in crime, who sure enough goes by “Butch.” So Butch and Sundance escape back to Seattle.

This escape infuriates Vic, so he buys an airline ticket to Seattle, hoping to chase down the criminals. At the airport, Tot gently chides him, “Two things drive you — anger and curiosity. I sense that the anger is in control. I wish it were the curiosity.” Rodor leaves, and Vic picks up a little reading material for the flight: Watchmen. Not surprisingly, he tunes into Rorschach, thinking, “Maybe a bit over the edge, maybe a little bigoted and he sure as hell is angry, but he does have moves.” Vic dozes off in his seat, and dreams the end of #15, but with himself as Rorschach, complete with crinkle-edged speech balloons and italicized text.

Almost immediately after arriving in Seattle, Vic gets drunk with an underworld type, attempting to get information, only to get himself badly beat up by that same guy. He eventually wins the fight, and steals his attacker’s ID. As The Question, he drives up outside the thug’s house, and thinks, “I could sit here in this rental car and keep an eye on the bastard’s house until something happened. But I ask myself, what would Rorschach do? He’d kick ass.” So The Question dives through the picture window, threatens the dude, and then gets clocked by a partner who was also in the house. On orders from Butch and Sundance, the two guys drive him up into the wintry mountains, planning to break his arms & legs and then let him freeze to death. Sitting in the car, he thinks, “Tot said my anger was in control and he was right and when I’m riding anger I make mistakes. Stupid mistakes. Why didn’t I listen?”

The Question manages to leap out of the moving car, and flees into the snowy wilderness, thinking to himself, “How did Rorschach end up? Oh yeh… dead. He ended up a wet spot in the snow. Why’d I have to remember that? Why do I have to keep learning the same lessons over and over? Being tough is not enough…” Then the wounded, exhausted, and frozen Question collapses. The thugs find him, and one points a gun at his head, saying, “Any last words?” The Question’s reply: “Yeah. Rorschach sucks.” Then a sudden surprise rescue from Green Arrow, and finis for that issue.

So now we have a triangle, its three points being Ditko’s Question, O’Neil’s Question, and Moore’s Rorschach. Ditko’s creation was the wellspring and inspiration for both of the other characters, and this issue draws the line connecting those characters to each other. As a means of character development for O’Neil’s Question, it works very well. One of the book’s major themes is Vic’s search for identity — as an orphan and a wanderer among philosophies, The Question’s central question is, “Who am I?” In that context, of course he’d explore adopting a persona based on this funhouse reflection of himself.

The trouble is, Vic does a terrible job of reading Watchmen. His takeaway about Rorschach seems to center on violence, anger, and toughness. It’s almost as though he has Rorschach mixed up with The Comedian. As a result, he misses the attribute of Rorschach which is most opposite Vic himself: his certainty. Rorschach is not seeking identities — ever since the Blaire Roche case, his identity is rock-solid. He knows exactly what he stands for and never wavers, much like Ditko’s Question. He’s about the last person in his universe who would ever say something like, “Maybe there are no heroes… and no villains, either.” Putting those words in Rorschach’s mouth shows us just how much distance is between those two points in our triangle.

The next incident also underlines their differences. Where Rorschach threatens and injures criminals in an attempt to get information, Vic tries to buddy up to them, only to get injured himself. Can you imagine Rorschach ever offering to get drunk with a criminal? Or for that matter, a common thug getting the jump on him? Where Vic isn’t sure what to do, and therefore tries new methods, Rorschach knows exactly what his methods are, and does not waver from them.

Those methods, I would argue, do not include charging into unknown situations to “kick ass.” Most of the times we see him go into action — investigating Blake’s death, hiding in Moloch’s fridge, eliminating Big Figure and his henchmen in jail — he is quite deliberate about everything, and appears to have thought through the angles either ahead of time or very quickly. Even when we see him act spontaneously, such as his cooking fat attack, he’s not acting impulsively — his facial expressions and body language are placid. Malcolm Long’s description of the subsequent actions says that they “dragged” Rorschach away from the scene, which suggests fighting or agitation, but immediately afterwards, he says that Rorschach “spoke to the other inmates.” Not screamed, not shouted… merely spoke.

We see an angry Walter Kovacs, but Rorschach’s affect remains flat, be it in therapy, jailbreak, interrogation, contemplation, or trying to save the world. Only at the very end, when he knows he’s about to die, does his composure shatter. He becomes a wet spot in the snow, but not because of his anger. His demise results from having so much of what O’Neil’s Question lacks: certainty. Vic, on the other hand, gets himself into trouble by letting his emotions rule him, and wavering from his convictions. He leaves Objectivism behind, he leaves meditation behind, he leaves moral clarity behind, and reaches out desperately to a book to help him find direction. But because of his unskilled interpretation of the material, that direction leaves him bleeding in the snow, and thinking that Rorschach sucks, when in fact, the main thing that sucks is The Question’s reading comprehension.

Next Entry: Across The Universes

Previous Entry: Who’s Down With O.P.C.?

Endnotes

1 Ditko himself was mostly doing short stories for indie presses at this time. [Back to post]

2 Released in the same month as Watchmen #6. [Back to post]

3 Something about the diving reflex, and the bullet being so low-caliber that it failed to damage Vic’s brain, and his mask slowing the slug, and Shiva being “as skilled at healing as she is at harming.” Not that logic really enters the equation much when it comes to the resurrection of comic book superheroes. [Back to post]

4 Real cities do sometimes show up in the DC Universe. [Back to post]

Leave a Reply