Greetings, fellow Watchmenites. I have not been derailed, merely distracted. It’s crazy how fast six months can go by. Doesn’t seem like it ever used to happen that way twenty years ago, but then again, it’s crazy how fast twenty years can go by. In any case, it’s been a while. Sorry about that, but I did have a lot of reading to do. Let me tell you why, and as usual, I warn that Watchmen spoilers are ahead.

For the first time since this project began, I’m jumping a considerable (well, comparatively so) gap in the Annotated Watchmen v2.0 While the last couple of references, which turned out to be more or less red herrings, were on pages 12 and 15 of Chapter 1, we now jump all the way to page 23, having completed Rorschach’s tour through the main cast:

Now that we have met the main characters, it’s useful to look at the characters that they are loosely based on.

Moore’s original plan for Watchmen was that it would involve the Charlton Comics heroes, whom DC had purchased from the defunct Charlton in the early 1980’s. DC eventually decided to insert these characters into its own super-hero universe, leaving Moore to rework the characters in Watchmen. The Charlton characters and their Watchmen analogues are as follows:

- The Question: Rorschach

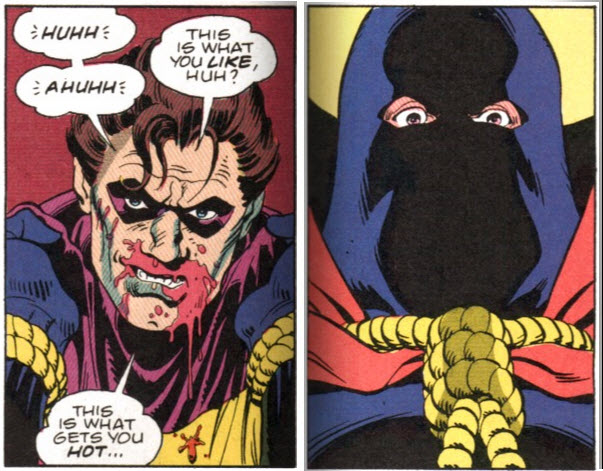

- The Comedian: The Peacemaker, though the Comedian shares some attributes with Sarge Steel as well

- Nite Owls I and II: Blue Beetles I and II

- Silk Spectre: Nightshade

- Dr. Manhattan: Captain Atom

- Ozymandias: Pete Cannon, Thunderbolt

The annotations then go on to briefly describe each Charlton character, but I’m not quoting that part, because I’m going to cover the same ground, albeit with trademark superverbosity. But first, a little history.

Once upon a time, in a town called Derby, Connecticut, there was a publishing company. Founded by Italian immigrant John Santangelo in 1931, the company’s first business was publishing lyric books for current popular songs. Unfortunately for Santangelo, this business model was illegal, and he ended up with a year-long jail term in 1934 for copyright violations. In the pokey, he met an attorney named Ed Levy, and the two went into business together after paying their debt to society. They both had sons named Charles, which is how the name “Charlton” came to be. They got hold of an old cereal box printing press, and made it part of a publishing venture. Where other companies contracted out for printing and distribution, Charlton put everything under one roof. They published (legal) music magazines (including the long-lived Hit Parader), fiction magazines, crossword puzzles, and, yes, comics. They published all kinds of comics — science fiction, funny animals, licensed properties (e.g. The Flintstones), crime, romance, war, horror, and when the circumstances dictated, superheroes too.

They were never a prestigious comics company, and they paid some of the lowest page rates in the business. In fact, the main reason that they published comics at all was that it was cheaper to do so than to shut the presses down, or so the story goes. Consequently, they were never known for their quality — writers and artists pounded out work quickly in order to make a living at such low wages. Nevertheless, for a time Charlton was a place where talented creators could hone their craft at the beginnings of their careers. Because the audience was small and the work high-volume, beginners could acquire a great deal of practice with a low public profile, and earn a few bucks in the process.

One of these beginners was a gifted, serious artist named Steve Ditko. Ditko did his first Charlton story in 1954, and continued working for the company throughout the 1950s, illustrating eerie tales and science fiction stories with an unusual flair and distinctiveness. However, after enduring a bout of tuberculosis in the mid-50’s, Ditko began taking side work at another company: Atlas Comics, which was soon to become Marvel. Ditko turned out the same kind of stories for Atlas as he did for Charlton, though at the former he was partnered with a veteran comics writer named Stan Lee.

As the 1960s dawned, superheroes were starting to gather a bit of steam again, so Ditko collaborated with Charlton writer Joe Gill to create a new superhero for the atomic age: Captain Atom! More about him later. Over at the company now known as Marvel, Ditko and Lee also got together to create a quirky superhero, whose debut was exiled to the final issue of an ailing anthology series called Amazing Adult Fantasy.

This was the birth of Spider-Man, one of the most famous and successful superheroes of all time. Month after month, Ditko and Lee turned out compelling, surprising Spider-Man stories, in the process generating an enduring supporting cast and rogues gallery for the instantly popular hero. They also collaborated on an even weirder creation: Doctor Strange, Master of The Mystic Arts, whose journeys through surreal extradimensional landscapes had college kids convinced that Ditko must have been on drugs.

The joke was on them, though, because not only was Ditko sober, he was straight and rigid as a steel arrow, and an arch-conservative Ayn Rand follower to boot. Lee, on the other hand, was a classic New York liberal, and not only that, he adhered to the notion that credit for a character’s creation should go solely to the writer. So as Spider-Man’s popularity skyrocketed (along with the rest of the Marvel line), the die was cast for these two guys to come into conflict. In fact, they weren’t even on speaking terms for the last year or so of their Spider-Man run, meaning that Lee would provide a line or two of plot summary, then Ditko would turn in full pages of art, into which Lee had to figure out how to slot his captions and dialogue.

When Ditko finally left, after Spider-Man #38, he never publicly said why. Onlookers have speculated about political conflict, character ownership claims, royalty disputes, and even a disagreement over the true identity of the Green Goblin. We will likely never know, as Ditko became more or less a media recluse, refusing most interviews and most questions.

What we do know is that after leaving Marvel in 1966, he returned to Charlton. By this time, he’d secured his place in the pantheon of legendary superhero artists, and a new Charlton executive editor named Dick Giordano wanted to capitalize on the opportunity. Thus was born the Charlton “Action Hero” line, including four Ditko-drawn heroes: Captain Atom, The Blue Beetle, The Question, and (briefly) Nightshade. To these, Giordano added other creators’ characters, such as Joe Gill & Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker, Peter A. Morisi’s Thunderbolt, Gill & Frank McLaughlin’s Judomaster, and Pat Masulli’s Sarge Steel. Sadly, while the Action Heroes line had its fans, it couldn’t sustain itself, and by the end of 1967 the whole thing had been scrapped.

What we do know is that after leaving Marvel in 1966, he returned to Charlton. By this time, he’d secured his place in the pantheon of legendary superhero artists, and a new Charlton executive editor named Dick Giordano wanted to capitalize on the opportunity. Thus was born the Charlton “Action Hero” line, including four Ditko-drawn heroes: Captain Atom, The Blue Beetle, The Question, and (briefly) Nightshade. To these, Giordano added other creators’ characters, such as Joe Gill & Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker, Peter A. Morisi’s Thunderbolt, Gill & Frank McLaughlin’s Judomaster, and Pat Masulli’s Sarge Steel. Sadly, while the Action Heroes line had its fans, it couldn’t sustain itself, and by the end of 1967 the whole thing had been scrapped.

Fast forward to 1983. By this time, Giordano had left Charlton, and had in fact become editor-in-chief at DC Comics. Charlton itself had fallen on hard times, publishing only reprints of its old material year after year. DC Executive Vice President Paul Levitz bought the rights to the entire Action Hero line from Charlton, as a gift to Giordano, who was encouraged to use the characters however he pleased.

Meanwhile, Alan Moore was contemplating a superhero murder mystery with established characters, and mapped out a pitch based around the recently acquired Charlton heroes. Giordano, wanting to use the characters as a part of the mainstream DC universe, balked at the changes that Moore’s storyline would force upon them, and encouraged Moore to create new characters for his project. And so here we are, with a book full of characters who share DNA with their Charlton ancestors, but who have also mutated in important and interesting ways.

Let’s look at each Charlton action hero in turn, along with how they map to their Watchmen analogues. In this entry I’ll focus on the Ditko characters, and then next time around I’ll pick up the rest.

Captain Atom

Captain Atom premiered in March of 1960, as the heroic alter ego of… Captain Adam, an eye-roller of a “secret” identity name if there ever was one. Captain Allen Adam, at least as he’s described on the first page of his origin story, is pretty superlative even before he gets his powers: “the Air Force career man who knew more about rocketry, missiles, and the universe than any man alive… a specialist of the missile age, a trained, dedicated soldier who was a physics prodigy at eight, a chemist, a ballistics genius!” For some reason, this invaluable genius is inside an Atlas missile, making final adjustments with just three minutes until blast-off. Wouldn’t you know it, he drops the screwdriver and can’t extricate himself in time, so he is launched into the stratosphere alongside an atomic warhead, preset to explode in space.

And explode it does! Captain Adam is disintegrated, but… “at the instant of fission, Captain Adam was not flesh, bone and blood at all… the desiccated molecular skeleton was intact but a change, never known to man, had taken place!” In point of fact, he mysteriously reintegrates, but as a (literally) radioactive man. His first task is to find himself a suit that will protect others from his radioactivity, and so his military buddies fetch him something called “dilustel”, which “converts the escaping rays to another frequency in the light spectrum.”

Captain Atom possesses a wide variety of powers, some of which seem to fluctuate at the writer’s whim. There are a few constants. He can fly and survive outer space like Superman. He can disintegrate and reintegrate to phase through solid matter. He can project heat from his body, and is strong and invulnerable. Otherwise, he can do whatever the plot needs him to do.

The main theme to Captain Atom stories is American superiority. Early on, these tended to take the form of short, fantastical red-baiters like “The Second Man In Space,” in which Captain Atom rescues a Russian astronaut who is dying in his capsule but ignored by Russian leaders on the ground, desperate to score a propaganda victory over the USA. (The astronaut lands safely and proclaims that an American saved him, meaning that the Russian was not the first man in space, hence the title.)

Later, the Captain turned his attention to marauding aliens, and finally, in the 1966 revival, to supervillains like Doctor Spectro, Thirteen, and The Ghost. Throughout all his stories, he remains a military officer whose loyalty is to the United States government. Even the supervillainy of his supervillains tended to be along the lines of “I stole some of the Air Force’s valuable equipment!” (In fact, his most frequent nemesis The Ghost was that worst of all blackguards, a former military adviser turned traitor.) All of CA’s victories, whether over Communists, aliens, supervillains, or rogue asteroids, were assertions of American invincibility1, and when they were complete he always returned to his life as Captain Adam, USAF.

Like Allen Adam, Jon Osterman has considerable scientific knowledge, and like Adam, he finds himself locked in an inescapable chamber upon which the power of Big Science is unleashed. Osterman is similarly disintegrated, and then reassembles himself again, albeit rather more gradually and gruesomely than does his predecessor. Finally, like Captain Atom, Dr. Manhattan can do pretty much anything he wants to, and for a time he even does it in the service of the United States government, lending it the same air of total indomitability.

Such are the similarities. But the differences mean more. Where Captain Atom is a military captain, representing armed aggression and might, Doctor Manhattan is an academic Doctor of Philosophy, representing intellectual inquiry and the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. Consequently, the Doctor soon loses interest in the kinds of hegemonic operations that occupy the Captain, moving his sphere of exploration to another sphere altogether. In any case, the Doctor’s government is a far cry from the unquestioned source of good that government represents in the Captain’s world.

Moreover, Dr. Manhattan’s persona takes Captain Atom’s godlike powers to their logical conclusion of godhood. For someone who travels among the stars and witnesses the wonders of the universe, the Captain seems content to keep his energies focused on the rather small beer of supervillain battles and national defense. The Doctor, on the other hand, comes to view such topics with utter indifference, finding fervency only in quantum miracles and the spontaneous creation of life. Reflecting this schism, the American people love the Captain2 but are utterly terrified of the Doctor, and perhaps rightly so. They realize that his loyalty is not to the United States nor even to humanity, and that therefore their own safety hangs always by the thread of his whims.

Nightshade

In issue #823 of the rebooted Captain Atom, the Captain picks up a partner. This is a heroine named Nightshade, “The Darling Of Darkness.” Nightshade is basically the punching kicking type, but she does have the superpower to change into a shadow (although she hates to do it), and also carries an arsenal of stuff like “ebony bombs” and a “black light gun.”

Of all the Charlton heroes, she bears the least resemblance to her Watchmen counterpart, and for good reason: Moore has said that he found her the least interesting, and that he patterned Silk Spectre II more after heroines like the Phantom Lady and the Black Canary. Stay with me though, because it’s still worth looking at how Nightshade herself made her way into the character of Laurie Juspeczyk.

Nightshade didn’t have too many Charlton appearances. She was created by Ditko and Joe Gill for Captain Atom, but she only showed up in a handful of issues before that series was canceled. However, she did have three solo stories as a CA backup feature, written by Dave Kaler and drawn by future Batman artist Jim Aparo. The predominant theme of these stories was childhood trauma, specifically centered around the character’s mother. Eve Eden is a senator’s daughter and jet-setting party girl, but this is merely a front for her deadly serious vigilante activities as Nightshade. She trains relentlessly on different fighting styles under the tutelage of Tanaka, also known as Tiger, the former sidekick of Judomaster4. (More on Judomaster next time.)

Why is she so driven, and why the deception? Well, it turns out that Nightshade has a nightmare in her past. One day when her father was away, her mother Magda brought Eve and her brother Larry into a room, drew the curtains and turned out the light. She explained that “once I was a princess in the land of the nightshades! And you’ve inherited the power of the royal nightshades from me!” She had fled this fairy/fantasy world because of a monster called The Incubus. So, for some reason, she decides to take her kids back to that land, and who should immediately show up but minions of The Incubus himself? They seize Magda, who yells at the children to run away and turn into shadows. Eve successfully does so, for the first time in her life, while the demons kill Magda in front of Larry.

Eve runs toward Magda, who grabs her hand and uses the last of her power to bring Eve back to our world, then dies, but not before extracting a promise from Eve that she will never tell her father, and will go back for Larry. Unfortunately for Nightshade, the Action Heroes line was cancelled before she could ever fulfill this promise. It wasn’t until years later, after the character had been well-integrated into the DC universe, that the story continued, albeit with slightly altered post-Crisis continuity.

So it’s true that Silk Spectre II does not have the power to turn into a shadow, or do anything supernatural at all. She is no princess from the land of the Nightshades. But what she does have is a mother who, recklessly and unwisely, drew her into a mysterious and shadowy world at a very young age. Sally Jupiter doesn’t bind her daughter with a dying wish, but she certainly makes it clear what she intends for Laurel to do, and the obedient girl tries her best to live up to that demand. Thus begins her life as an adjunct, first to an atomic-powered superhero and then to a millionaire gadget freak. Her powers and her look may have been based more on the Black Canaries of the world, but the legacy of Nightshade lives on in Silk Spectre II.

Blue Beetle

“Millionaire gadget freak” is a nice transition to Ditko’s Blue Beetle, but first we must once again hop into the wayback machine. Further back, I mean.

The Blue Beetle didn’t start out at Charlton. No, he was created in 1939 at a company called Fox Comics. Here, let’s ask Jim Steranko to slip into comic book historian mode and tell us about it:

Fox Publications was the poverty row of comic books and their superheroes were completely derivative. Their most important hero was the Blue Beetle. I remember one day I talked to Charlie Nicholas, the creator of the Blue Beetle, and I asked him what was it that inspired him to create this rather unusual character named after a bug. And he explained everything about the Fox mentality to me in two words: Green Hornet.

So Blue Beetle began as a pulpy masked detective, but very quickly morphed into an extremely generic Superman clone. His civilian identity was Dan Garret, rookie cop, who made sure to bumble through his job so that nobody would suspect his secret. He got pestered by a girl reporter, who was suspicious about all his disappearances. Sometimes he took something called “Vitamin 2X” to turn into the Blue Beetle, and sometimes he just changed without any help at all, with perhaps a handwave to radioactivity maybe being the source of his powers somehow. His stories were almost incoherent, at least to my modern eye — very stylized and elliptical. He’d acquire new superpowers every issue, whatever happened to fit the plot, but he was always your basic flying, invulnerable, super-strong guy with eye powers like x-ray and heat vision.

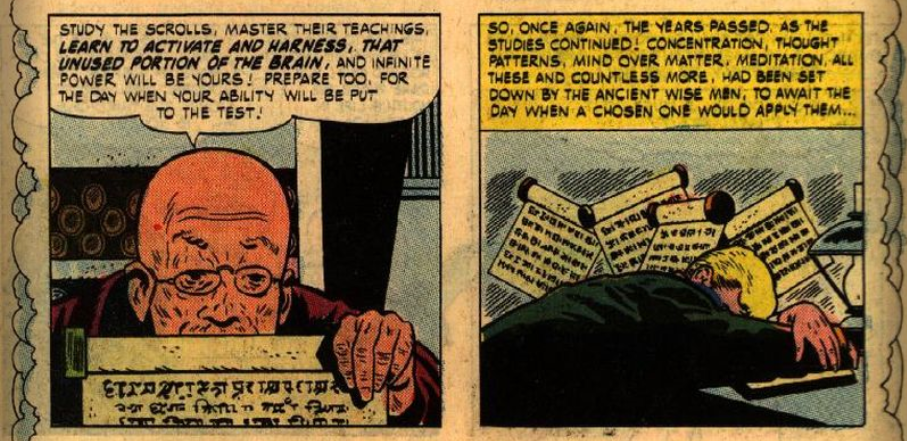

By 1950, Fox had crumbled, and its assets were put up for sale. Charlton picked up the rights to the Blue Beetle, and reprinted stories from Fox’s inventory. These didn’t catch on, though, and it wasn’t until 1964 that Blue Beetle saw the light of day again, this time in a reboot from Joe Gill and Tony Tallarico. In this second incarnation, Dan Garrett (who had somehow picked up an extra “t”) was no longer a rookie cop, but was instead one of those comic book science types who knows everything about everything. He’s ostensibly an archaeologist, but can produce knowledge of physics, chemistry, linguistics, or whatever as the plot demands it.

This time around there’s at least a clear explanation for his powers, which he acquires when investigating a pyramid. He opens a casket, which releases the kind of great evil for which pyramid caskets are famous worldwide. However, he also finds a scarab nearby. When he picks up the scarab, he has a vision of a mighty ancient pharaoh, who tells him it is now his duty to fight evil as the Blue Beetle.

He’s still no less derivative — his base powerset is flight, x-ray vision, strength, invulnerability, and heat vision. And again, he displays random new powers on cue from problems in the story: he can “transmit electrical energy” past a broken wire or use his “micro-vision” to analyze broken machinery. However, he’s not just derivative of Superman — he also gets a Captain Marvel code word (“Kaji Dha!”) to say whenever he wants to switch back and forth between identities. Or sometimes clasping the scarab itself gives him his powers. It varies.

This Blue Beetle ran out of steam in early 1966, and so the character was shelved for a while. But a few months later, in the back pages of Captain Atom #83, an entirely new Blue Beetle took the stage, created and drawn by Steve Ditko. This one wasn’t Dan Garret(t) at all, but was instead a (you guessed it) millionaire gadget freak by the name of Ted Kord. Kord had a more interesting costume than the previous Blue Beetles, and his fighting style was dynamic and acrobatic, in the vein of Spider-Man. However, Kord had no superpowers, relying instead on a bug-shaped airship which ferried him from one crime scene to the next, entering and exiting his secret lab via an underwater entrance. Along with his fists, he used a variety of high-tech gimmicks designed to protect himself and beat up the bad guys.

So where did this new Blue Beetle come from, and what happened to Dan Garret? That’s just what the police would like to know, in an ongoing subplot depicting dogged Irish cops from Central Casting, who hassle Kord and his lab assistant/paramour Tracey about Garret’s disappearance. Readers are kept in the dark too, at least until the new Blue Beetle gets his own series in the summer of 1967. Issue #2 of this series reveals all. It seems that back when Kord was a junior scientist, he fell in with his Uncle Jarvis, working as a lab assistant and doing mysterious tests. Jarvis is mum about the purpose of his work, but Kord’s genius helps him solve all his operational problems. Finally, the lab explodes, with Jarvis apparently inside, and Kord uncovers the true purpose of his work: to create unstoppable super-strong androids. He also finds a map, to the mysterious Pago Island.

Kord, conflicted and confused, turns to his mentor, a college professor by the name of… Dan Garret. (Who once again seems to have lost his extra “t”.) Kord strongly suspects that his uncle faked his death, and is completing his scheme on Pago Island. He and Garret agree to investigate, and indeed they find an army of androids on the island. Garret becomes the Blue Beetle to fight them, but is killed when Jarvis makes his robots self-destruct. As Garret is dying, he makes Kord promise to keep his secret and carry on the legacy of the Blue Beetle. Legacy is, in fact, the overriding theme of the Ditko Blue Beetle stories. Kord decides to use his genius to whip up a fancy ship and an arsenal of crimefighting tools, and a new superhero is born.

Moore mashes up various parts of this story to make Nite Owl. Like the early Blue Beetle, the first Nite Owl is also a cop, though there’s no mention of the incompetence ruse. Such a tactic probably wouldn’t last long in Watchmen‘s more realistic milieu anyway. And like the latest Blue Beetle, Dan Dreiberg is a brilliant tinkerer whose closets are bursting with suits and gizmos for crimefighting. Archie the owl-ship is pretty much a copy-and-paste of Blue Beetle’s bug-ship, right down to their propensity for dramatically emerging from beneath the waves.

As with the Blue Beetle stories, the idea of legacy permeates the Nite Owl stories. The first time we see Dreiberg, he’s reverently absorbing hero anecdotes from the first Nite Owl, Hollis Mason. There’s clearly a warmth to the relationship, and Dreiberg later tells Laurie Juspeczyk that he idolized Mason. As he says, “I guess that’s pretty obvious.” There’s no Pago Island and no heroic sacrifice — in fact, Dreiberg just approached him as a fan and asked for the use of the name Nite Owl. However, the elder Nite Owl does end up dying violently, and as with Ted Kord and Dan Garret, the mentor’s death is an indirect result of the protege’s actions, in this case freeing Rorschach from prison.

It’s not just Mason, though. Dan Dreiberg is a throwback in all kinds of ways. He doesn’t listen to Devo — he listens to Billie Holiday and Louis Jordan. He wishes the Crimebusters meeting would have worked out, because he wants to belong to a “fellowship of legendary beings” like the Minutemen, or the Knights of the Round Table. He wonders aloud what’s happened to the American Dream. He’s trying not only to carry on the name and legacy of Nite Owl, but to carry on the Golden Age ethos as a whole. Like Blue Beetle, he wants to extend a tradition, and as with Blue Beetle, it doesn’t always work out so well.

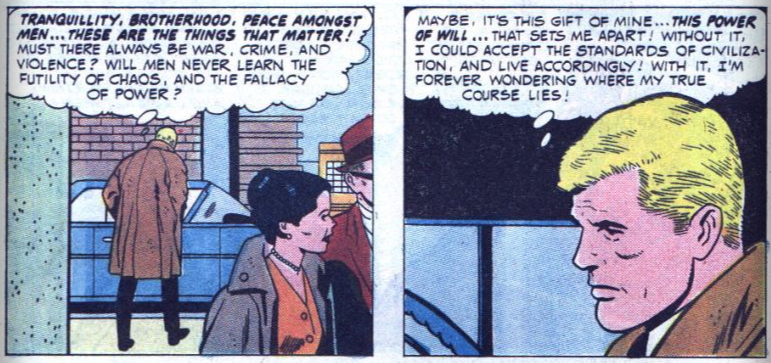

The Question

Just as the newest Blue Beetle began as a backup feature for Captain Atom, The Question began as a backup feature for Blue Beetle. The cover of Blue Beetle #1 (volume 4, that is) dramatically asks: “WHO IS THE QUESTION?” I’ll tell you: The Question is the most Ditko-esque Charlton hero of them all. Vic Sage is a “hard-hitting TV newscaster.” (Gosh, that sounds awfully dated now, doesn’t it?) He’s not afraid to ask the tough questions, not afraid to hold people strictly accountable for their actions. He alienates many of his co-workers by being so unflinchingly dedicated to the Truth, so unwilling to compromise his principles one iota. Moral weaklings are constantly trying to get him to avoid controversy, which he nobly refuses to do. Consequently, his enemies at the TV station (who fear the loss of revenue that controversy could bring) keep trying to get him fired, but his friends are completely loyal, as is the station owner. And yet, his excellence is all too often unfairly ignored by a docile and apathetic public.

When it appears that the relentless broadcast Honesty of Vic Sage isn’t enough to bring down the forces of corruption and venality, Sage slips into a secluded place and applies a latex mask to his face, which obscures his features. He then releases a special gas invented by a Professor Rodor. The gas binds the mask to his face and changes the appearance of his clothes to a pale blue. He beats up the bad guys, and freaks them out as the eerie gas flows from his hands, revealing hitherto unseen question marks on innocent objects. A precursor to clench-jawed vigilantes like The Punisher, he gleefully sends criminals to the electric chair, or kicks them into the sewer and lets them drown.

In case it’s not clear, the overriding theme of all The Question’s stories is Objectivism. Like Ayn Rand, Vic Sage (whose 3-letter/4-letter naming pattern is surely no accident) holds that morality is not relative but absolute. He adheres to a black-and-white set of principles that leaves no room for compassion (or as he would view it, coddling.) He ensures that his version of justice is always done, meaning that the criminals he has judged pay the maximum consequences for their actions. He also frequently asserts his right to control his own behavior, and of others to control theirs, as when he narrowly escapes an assassination attempt via bombing at the office. The station owner says, “I can’t expect anyone to face violence for me!”, to which Sage replies, “No one can force me to face violence! But neither can they stop me from facing it! That is my decision! What’s up to you is whether or not I’m allowed to continue broadcasting!”

Everybody talks like this in Question stories. It’s page after page of polemic, with Sage boldly declaiming Objectivist views on TV (“I repeat, rights can only belong to individuals! Groups, by themselves, have no rights! The rights belong to the individual within the group!”) while his enemies at the station say things like, “Why does he have to stir up so much trouble? With this many people against him, he must be wrong!” The criminals in his stories cry, “He deserves everything he gets! He didn’t have to pry into my affairs!”, and The Question laughs in their faces when they try to offer him a cut of their loot. Seriously, if he’d lasted long enough to establish an archenemy, it would totally have to be Strawman.

In Blue Beetle #5, the last published issue before the Action Heroes line was cancelled, Ditko lets loose completely. The villain of the Blue Beetle story is an art critic, Boris Ebar, who praises a depressing sculpture on the opening splash page, in a long speech peppered with references to “man’s inevitable weaknesses” and “man’s inability to solve or control the illusion we call existence.” Ted Kord (who, as the hero of the story, has suddenly become an Objectivist) is disgusted at this rejection of objective reality, and couldn’t be more pleased when Vic Sage (in a rare crossover appearance) tells the critic, “That thing and your views belong on a junk heap!” A depressed janitor adopts a costume to resemble the depressing statue, and goes around town trying to destroy more valiant-looking art, cheered on by a bunch of moral relativist hippies. Luckily, the Blue Beetle stops his downer rampage while an admiring Vic Sage looks on.

Then, in The Question backup story, that same Ebar tries to bring a depressing painting into Sage’s TV station (“It represents… the refusal of man to help his fellow man get out of the gutter!”), and as recompense for his gift asks for Sage’s termination. Then Sage’s loyal assistant Nora confronts the critic with a more noble and uplifting painting, which gets him so upset that he hires thugs to go into Nora’s apartment and destroy the painting. Luckily The Question is there to fight them off. In a final climactic scene, Nora again confronts Ebar with the bold painting, and he breaks down in tears, addressing the figure on the canvas: “Why won’t you let me lie to myself? Why do you keep making me see what I let myself become… stop it! I must destroy you… to destroy the proof of what I once wanted to be!” It’s the only superhero comic I’ve ever seen where heroic art defeats the villain, and it is just about as uptight and didactic as you could possibly imagine.

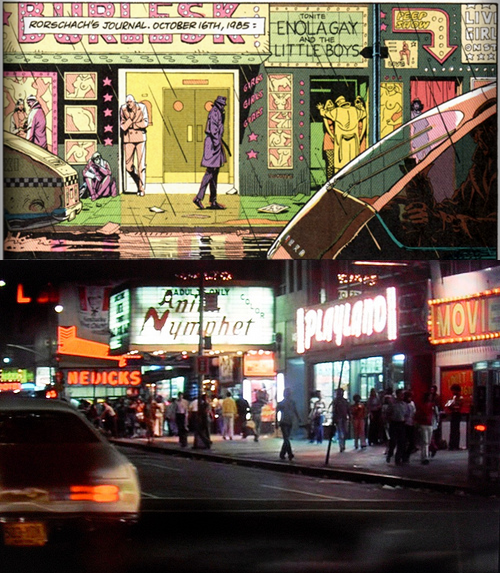

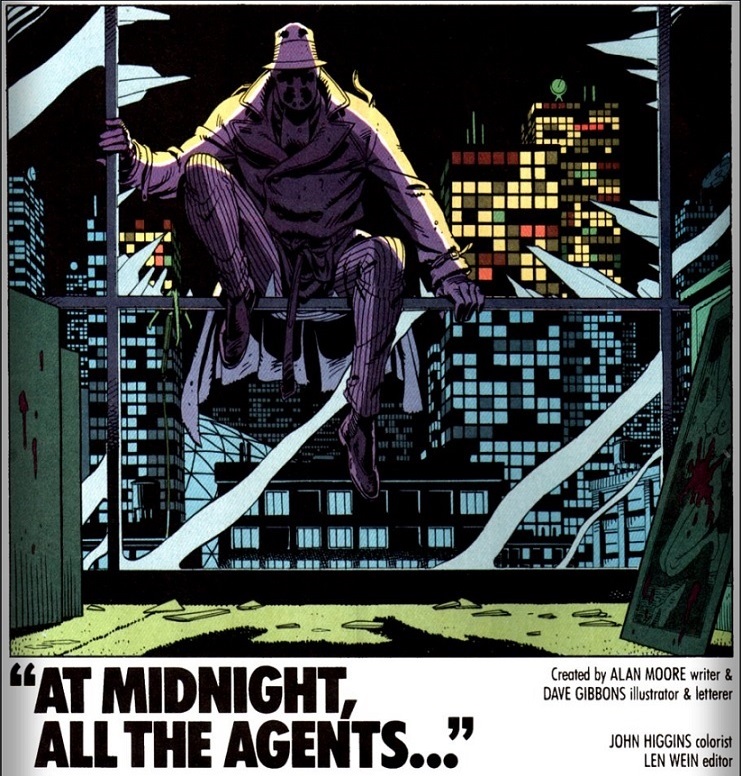

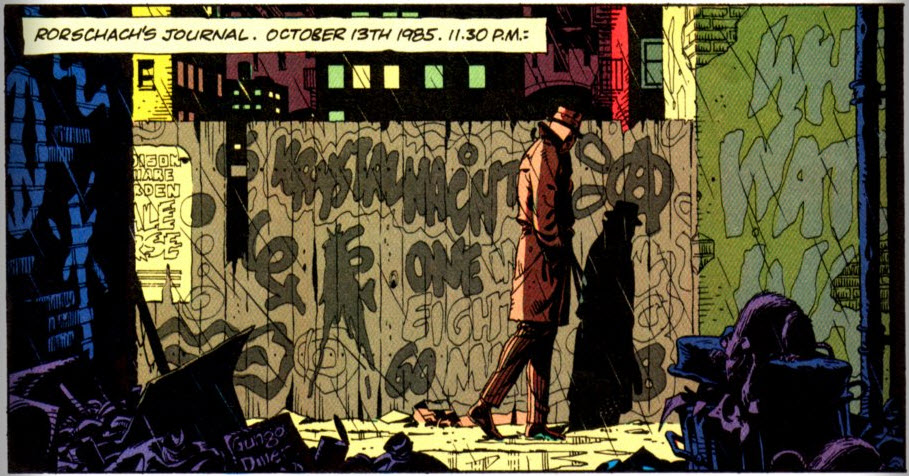

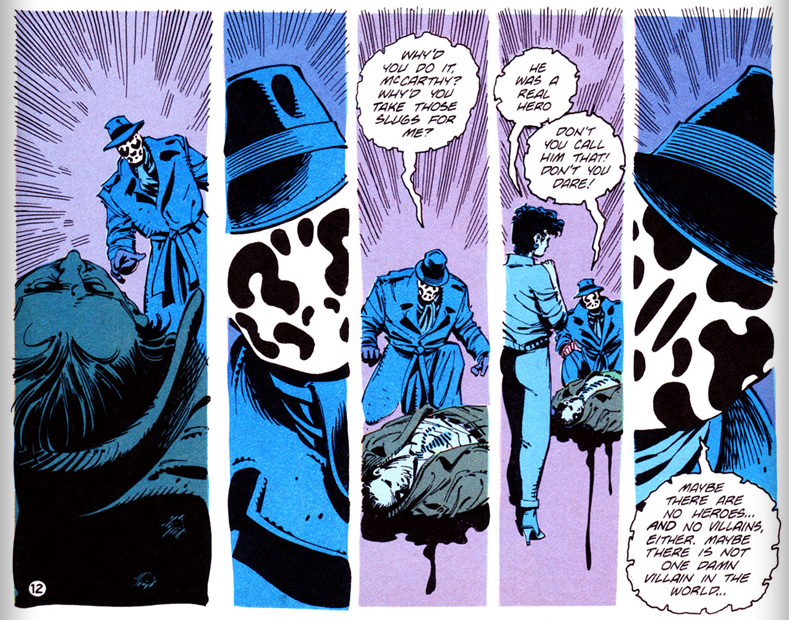

With Rorschach, Moore copies The Question’s absolutism and fierce sense of purpose, as well as his tendency to moralize, albeit to himself in a diary rather than to a city at large. (Well, perhaps that changes after the story’s final panel.) Like The Question, Rorschach sees the world in black and white (“…but not mixing. No gray. Very, very beautiful.”) Like The Question, Rorschach does not hesitate to maim or murder those he sees as scum — he’d just as soon drop a criminal down an elevator shaft as listen to him. And like The Question, he sees himself as a warrior for The Truth in a degraded and corrupt world.

The crucial difference is that Rorschach exists in a world of human beings rather than cardboard cutouts designed to represent caricatured worldviews. Those humans tend to view Rorschach as, well, insane. And with good reason. But Moore does not even let us off that easily.

Yes, Rorschach’s civilian “profession” of carrying a doomsday sign seems like a clear parody of Vic Sage’s televised proclamations. And yes, his tendency towards violence can seem extremely misplaced when applied to harmless cranks like Captain Carnage. And yes, his casual contempt for the majority of humanity is quite obviously at odds with his self-professed heroism. And yet.

And yet in the end Rorschach becomes arguably the most admirable figure in the story, as his refusal to sacrifice his principles in the face of Veidt’s monstrous deception gives him a level of heroism which none of the others can claim. Forget about the Keene Act — even in the face of Armageddon, Rorschach will never compromise.

Not only that, Chapter 6 lets us in on Rorschach’s own humanity, the horrors he has seen which make him the horror that he is. We see him as a child, weeping as abuse rains down upon him, furious as he strikes back at the cruelty around him. We see him shaped by a real incident (it’s vital that the incident be real) in which a docile and apathetic public is accessory to murder. We see the utter blackness of sadism and violent crime which brings out his absolute opposition.

In short, we see enough to understand Rorschach, and to have compassion for him. That compassion is the key to such a character is, perhaps, the final satirical twist on Ditko’s own stiff brand of storytelling, and on the Randian disdain for emotions.

There are more action heroes and more Watchmen counterparts to discuss, but this entry has certainly gone on long enough. Next time: Peacemaker, Thunderbolt, Judomaster, and Sarge Steel! I’ll try to take less than six months to write it this time.

Next Entry: Who’s Down With O.P.C.?

Previous Entry: No Voice Is Eternal

Endnotes

1 The one exception to this is the couple of stories where Captain Atom takes a paternalistic role to a young boy in trouble. In particular, a story called “The Boy And The Stars”, originally from Space Adventures #40, has Captain Atom taking a sick child “to a star which does not appear on maps of the solar system… a lovely star which emanates a ray that I have found useful.” There’s a particularly touching panel in which CA holds the boy’s hand as they stand in a fantastic landscape of swirling Ditko smoke.

[Back to post]

[Back to post]

2 Though in one issue of the 1966-67 revival, Captain Atom suffers a public backlash highly reminiscent of Spider-Man. [Back to post]

3Charlton’s issue numbering is notoriously weird, presumably from their attempts to skirt postal fees for new publications by changing the names of existing ones instead. So issue #83 of the rebooted Captain Atom is really the 6th issue of the relaunch, since Strange Suspense Stories was renamed to Captain Atom with issue #78. [Back to post]

4Crossovers between the Charlton heroes are rare, and their letter columns at the time explained this policy as intentional, saying that they wanted to focus on establishing their line of heroes before they started mixing them up. However, Nightshade seems to have been the exception to this — between the fact that she’s partnered with Captain Atom and the fact that she trained with Judomaster’s sidekick, her stories probably have the most connective tissue of all the Charlton stable. The uncharitable interpretation of this might be that writers believed there would be no interest in a girl character unless there was an already popular man in her stories. Or, to put another spin on it, she’s a minor character who just coincidentally happens to be the only female of all the “Action Heroes.” [Back to post]

What we do know is that after leaving Marvel in 1966, he returned to Charlton. By this time, he’d secured his place in the pantheon of legendary superhero artists, and a new Charlton executive editor named Dick Giordano wanted to capitalize on the opportunity. Thus was born the Charlton “Action Hero” line, including four Ditko-drawn heroes: Captain Atom, The Blue Beetle, The Question, and (briefly) Nightshade. To these, Giordano added other creators’ characters, such as Joe Gill & Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker, Peter A. Morisi’s Thunderbolt, Gill & Frank McLaughlin’s Judomaster, and Pat Masulli’s Sarge Steel. Sadly, while the Action Heroes line had its fans, it couldn’t sustain itself, and by the end of 1967 the whole thing had been scrapped.

What we do know is that after leaving Marvel in 1966, he returned to Charlton. By this time, he’d secured his place in the pantheon of legendary superhero artists, and a new Charlton executive editor named Dick Giordano wanted to capitalize on the opportunity. Thus was born the Charlton “Action Hero” line, including four Ditko-drawn heroes: Captain Atom, The Blue Beetle, The Question, and (briefly) Nightshade. To these, Giordano added other creators’ characters, such as Joe Gill & Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker, Peter A. Morisi’s Thunderbolt, Gill & Frank McLaughlin’s Judomaster, and Pat Masulli’s Sarge Steel. Sadly, while the Action Heroes line had its fans, it couldn’t sustain itself, and by the end of 1967 the whole thing had been scrapped.